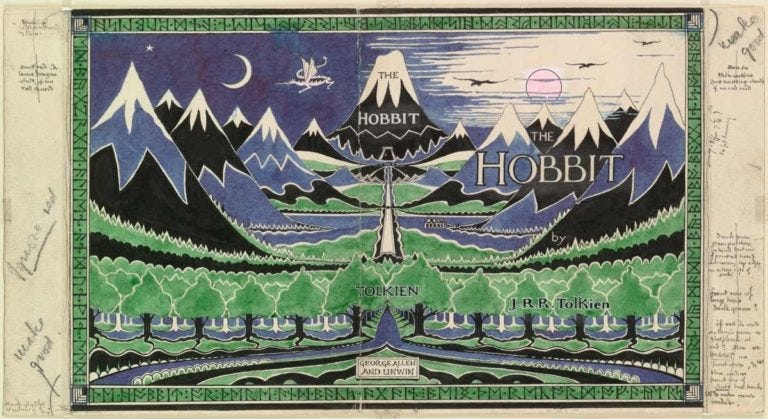

The Hobbit Alone

A Tale Outside the Legendarium of Middle-Earth

I recently came across this amazing blog post by Rise Up Comus entitled 1937 Hobbit As a Setting and the concepts presented in it have had me absolutely transfixed for months. Not only is this a great article about gamifying the material in the J.R.R. Tolkien classic, but the idea of taking world of The Hobbit as it was originally presented and using that as a setting unto itself is fascinating. This is The Hobbit completely divorced from the greater Middle-earth it was later retconned into and connected with. Looking at The Hobbit completely on its own and the world building done there is a fascinating exercise. Things immediately jump out at me that separate the world of The Hobbit from Lord of the Rings.

Humans are Not the Default: We hear what we assume is the description of humans fairly early on in the text with Gandalf stating he is looking for heroes but they are all absent or in far off lands - but they’re never started specifically to be so. We, as the reader, are making an assumption. Gandalf could be a human, but is never described as such. He is always and only a wizard. In fact, its not until we arrive in Dale that we encounter our first true humans. We are lead through the tale by a familiar, though ultimately inhuman protagonist and his 13 equally inhuman protagonists. By contrast most fantasy tales, including Lord of the Rings, are set in a world where humans are the dominant people.

Fairy Tales Abound: We catch references to classic fairy tale elements all the time. One of Bilbo’s ancestors is said to have taken a fairy wife. This is later contextualized in Lord of the Rings as a fantastic claim that it was an Elf - but as it stands on its own, this is a literal fairy when taken solely in the pages of The Hobbit. We hear of heroes rescuing princesses from dragons, the uncanny luck of widow’s sons, haunted castles dotting the landscape, and many other elements that are straight up fairy tale elements - including talking animals. These are largely absent or repurposed when the book is made part of the Middle-earth canon.

Gandalf is Just a Wizard. Those familiar with the lore of Middle-earth know that Gandalf, along with other wizards like Radagast and Saruman, are not mortal creatures. They are almost akin to angels incarnate with fantastic powers. But in the context of The Hobbit as a stand alone entity, Gandalf and the name-dropped but absent Radagast are “just” wizards. They’re not Maiar and for all we know, Gandalf may be human - though he is never identified specifically such. Wizardry is some talent or skill he has learned and never implied to be an inherent part of his nature. He even uses a wand in The Hobbit that is never mentioned as such in The Lord of the Rings.The Necromancer he departs Thorin’s Company to face is also never identified as anything more than, well, a necromancer. A magician who specializes in deathly spells and who is implied to be some great threat outside the direct context of Thorin’s quest for The Lonely Mountain. Interestingly enough, Elrond is never specifically named as “Elrond Halfelven” either. Indeed, he isn’t even explicitly named an elf, only “there were still some people who had both elves and heroes of the North for ancestors, and Elrond the master of the house was their chief. “ So not truly an elf, nor truly a human - but an ancestor of a strange and undefined lineage full of heroes.

Magic is the Purview Many. While Gandalf is clearly more skilled in the art of magic than any other character we meet in The Hobbit, it is not an art exclusive to him. The dwarves use wards to protect the treasure they hide after plundering the troll caves. Bard the Bowman can speak with the thrush - an apparent sign of his rightful kingship over the people of Lake-Town. Beorn can communicate with, befriend, and draw into his service beasts ranging from bees to dogs to other creatures.

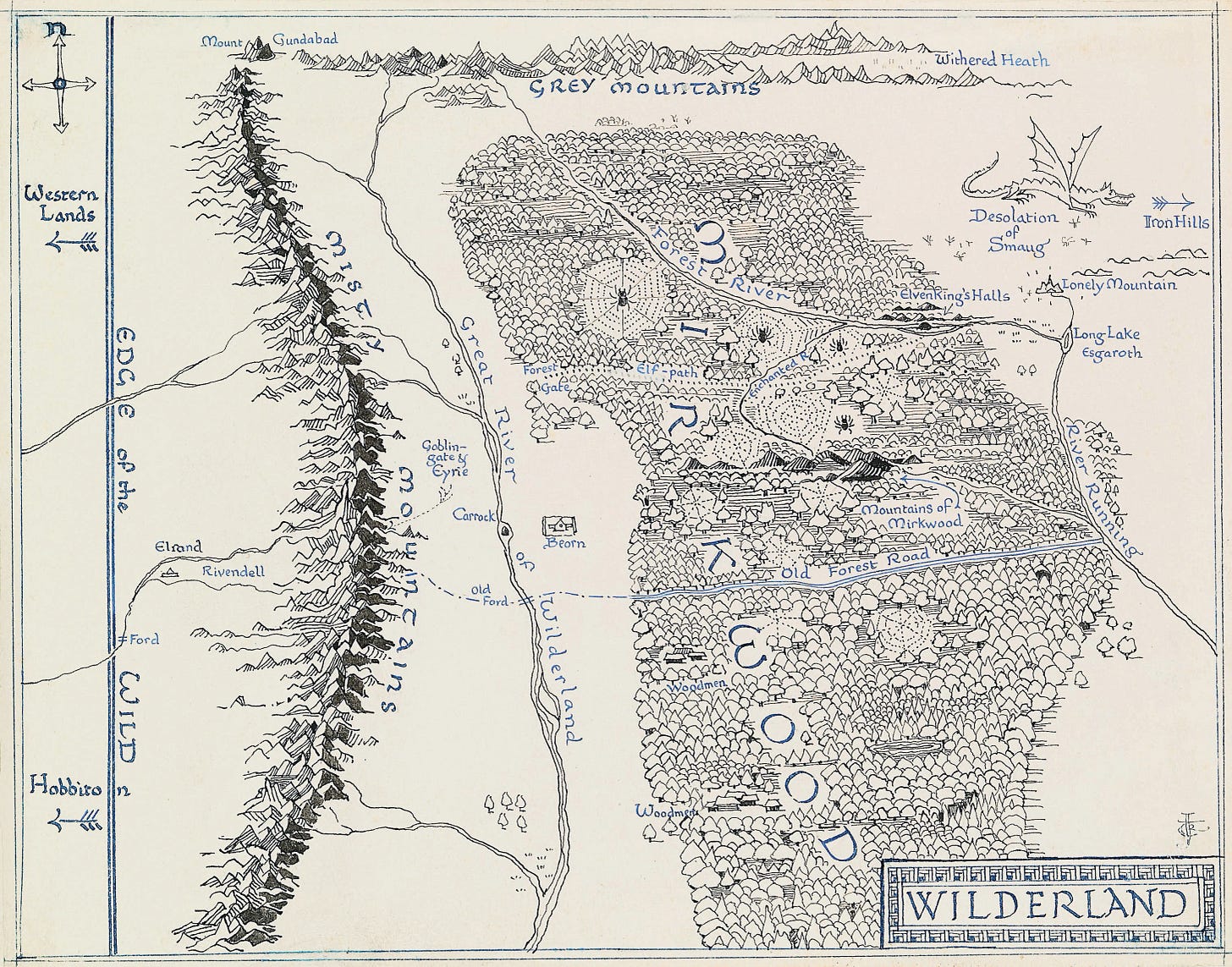

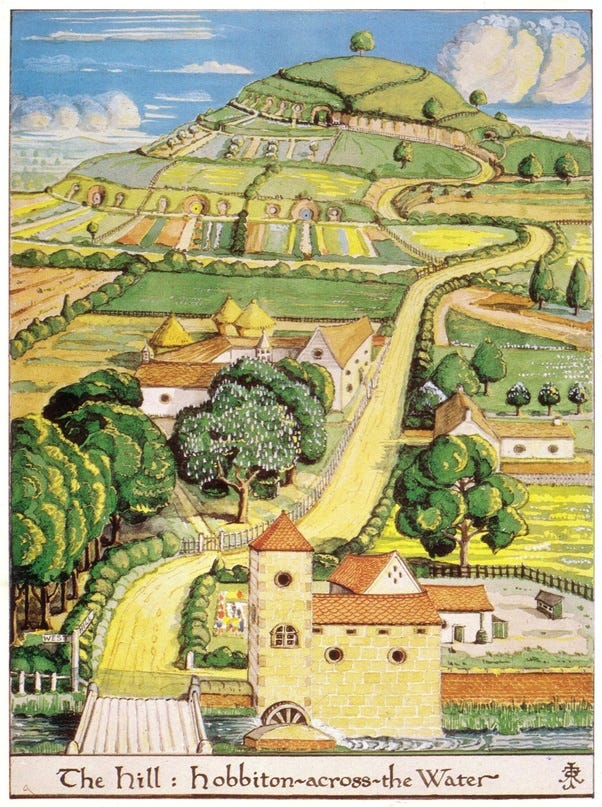

Names are Simple. I often forget that the name “The Shire” never appears as such in The Hobbit. The homeland of the hobbits as a people is implicitly nothing more than a small village or community. It has a specific name only in Tolkien’s own art for the book - Hobbiton. Literally “Hobbit Town.” One so small that Bilbo lives on The Hill and by The Water. This denotes a community so tiny that it needs no distinction to identify two significant landmarks that are both hills or likes. The homeland of the hobbits is tiny, rural and remarkably simple. The names we do get in The Hobbit are as often simple identifiers and less grandiose names. The valley where Elrond lives is indeed named as Rivendell, but in the text his home is identified as The Last Homely House -a simpler name that is used to specify the refuge itself and called out more often than the more exotic name Rivendell. Where do the goblins live? Goblin-Town. The town of Dale is a ruin whose name is simply an archaic word for “valley.” Where do the humans in The Hobbit live? Lake-Town - which is shockingly a town that is literally on a lake. Even the elves they meet live in Mirkwood - a mirky woodland. Even the name Erebor, the dwarvish name for The Lonely Mountain, is never called as such in The Hobbit. It is always called simply The Lonely Mountain. Even the weapons get simple names: Biter, Beater, Sting. Even the name Middle-earth never appears. Only Wilderland.

History is Implied, But Never Specified. Two exotic location names we do learn are Gondolin and Moria. The swords found in the troll hole were made in Gondolin by people known only as High Elves for their war against the goblins. We know nothing about when they were made, how they came to be in troll holes, how these wars came about, or the ultimate fate of Gondolin. Another such mysterious place is the Mines of Moria. We learn that Thorin’s grandfather Thror went seeking Moria and was eventually slain by Azog the Goblin - the only time his slayer is named. We don’t know why Moria is important, nor get any history as to its importance to the dwarves beyond it being a mine and therefore presumably wealthy. Again, we learn only that the goblins made war on the dwarves and the elves. The details are left for us to ponder.

Fairy Tale Monsters. There are no orcs in The Hobbit. Goblins, wolves, dragons, and spiders, and distant giants and foolish trolls - but all of these are firmly in the realm of fairy tale. We see no unnerving Nazgul, no Uruk-Hai, no demonic Balrogs. Indeed, we see no human adversaries either. At least not those allied with evil forces. The closest we get is the infighting that comes from the Battle of Five Armies. All of the monsters we encounter in The Hobbit have their roots in fairy tales and seem implicitly to have come from it.

Firearms Might Exist. Across The Hobbit, indeed from the first chapter, we hear reference to guns. Gandalf admonishes Bilbo for opening the door “like a pop-gun,” Gandalf casts a spell that leaves the smell of gunpowder explicitly, the roar of Beorn’s voice is described as being akin to “drums and guns,” and goblins are described as “not unlikely that they invented some of the machines that have since troubled the world, especially the ingenious devices for killing large numbers of people at once, for wheels and engines and explosions always delighted them.” Machines and explosions. In addition, clocks exist explicitly in the world of The Hobbit, as Bilbo has one on his mantle and even refers to being lost underground as a “clockless” place. The mantle clock was something that didn’t appear in England until the late 18th century.

This is a pre-history or fantastic era of Earth. In the first paragraphs of The Hobbit we receive a description of hobbits that includes the following: “…they have become rare and shy of the Big People, as they call us. They are (or were) a little people, about half our height, and smaller than the bearded Dwarves. Hobbits have no beards. There is little or no magic about them, except the ordinary everyday sort which helps them to disappear quietly and quickly when large stupid folk like you and me come blundering along.” There is a connection between hobbits, the world they inhabit, and our own world. In addition, the author, presenting themselves as a narrator, uses comparisons to modern technology repeatedly, like describing a scream let out by Bilbo that “burst out like the whistle of an engine coming out of a tunnel.”

Magical Items are Wonderful, Not Menacing. In The Hobbit, not only does Bilbo win the ring from a very different incarnation of Gollum that is later completely re-written to fit the Lord of the Rings, it is also just that: A ring of invisibility. It has no great lore, no secret past, no dark curse set upon it by the one who made it. The swords of Gandalf, Thorin, and Bilbo are also magical, and while they have more history behind them than Bilbo’s Magic Ring, they are still “just” magical. They are wonderful tools discovered by our protagonists and used to aid them on their quest - not dark MacGuffins.

Our Heroes are Quite Foolish. From the beginning, Frodo and his friends (and later, the Fellowship) are self-serious and offer a respect for the gravity of the task due them. They prepare and arm themselves appropriately, and are given gifts to aid them in their quest by allies who know what they are trying to accomplish. Not so, in The Hobbit. Yes, Thorin takes himself and his quest very important, but we see the dwarves are comedically under-prepared for facing a dragon and restoring a kingdom. Anyone with a modicum of sense would have difficulty believing an expert treasure hunter lives in a rural manor and gets flustered at dwarves tramping through his kitchen, but the dwarves are willing to look past all this (with some coaxing from Gandalf) and buy in to the fact that Bilbo is such an expert. Moreover, for all the gravity Thorin does lend the quest to restore The Lonely Mountain and the fact that they will have to face a literal dragon to do so, they planned on trekking across the entirety of Wilderland and all its dangers - including Smaug - without a weapon. Not a sword, an axe, or a crossbow among the lot. But they certainly remembered to bring their harps, lutes, and viols! This is no Hobbit walking party - but its almost as if the dwarves are treating it as such. Adventures in the world of the The Hobbit are a merry thing with few concerns for true danger, apparently.

There are just a few key elements of the world of The Hobbit that mark it as something very different from the world of Middle-earth. While these are the most evident differences between the original world of The Hobbit, there is one storytelling convention that really stands out in the book which is not present in Lord of the Rings. While it has a narrative through line in Thorin’s quest to reclaim the Lonely Mountain, the book is told in an almost episodic fashion with each chapter. Chapter breaks almost always denote a location change within the story and more over, the narrative of The Hobbit regularly moves from “Civilized Chapter” to “Wilderness Chapter.” Let’s take a look

Chapter One: An Unexpected Party - Location: Bilbo’s House, Civilized

Chapter Two: Roast Mutton - Location: Troll Camp, Wilderness

Chapter Three: A Short Rest - Location: The Last Homely House, Civilized

Chapter Four: Over Hill and Under Hill - Location: Mountains/Caves, Wilderness

Chapter Five: Riddles in the Dark - Location: Gollum’s Pool and Home, Civilized (comparatively, and for Gollum at least)

Chapter Six: Out of the Frying Pan & Into the Fire - Location: Caves/Wilderland, Wild)

Chapter Seven: Queer Lodgings - Location: Beorn’s House, Civilized (again, comparatively)

This pattern continues until the Dwarves depart Lake-Town. Once they enter the Mountain itself, danger surrounds them constantly, expressed in Bilbo’s riddle game, Smaug’s assault on Lake-Town, and the Battle of Five Armies. Each of these dangers is escalating in scale. Bilbo’s riddle game is personal between him and Smaug - though it reveals the dwarves to Smaug. The assault on Lake-Town directly endangers (and indeed implicitly kills) many of that town’s residents. Finally, the Battle of Five Armies puts almost every character we’ve encountered in the narrative up to this point at risk. The civilized has become wild. There is no safety to be had.

Using this method to give the reader a “pause,” between the excitement allows the author (and by extension the GM) introduce the world incrementally and without a huge sense of urgency. Each new fact of the specifics of the setting is introduced in a safe, civilized location where the knowledge gained can then be applied when one ventures back into the wild. By the time it’s “all wilderness,” Bilbo (and in an RPG, the PCs) are familiar and comfortable enough with the world to stand on a foundation of accumulated knowledge that’s slowly earned over time.

Most other fantasy settings, including Lord of the Rings take an alternate route by giving a massive dump of exposition and expecting the reader (or player) to somehow remember it all. In Fellowship of the Ring, you could almost call The Council of Elrdon “The Council of Exposition,” because that’s the purpose it serves in the narrative. No such thing in The Hobbit. We learn the inciting incident for both of our primary protagonists - Bilbo and Thorin - and we’re off.

But it works in The Hobbit (and not Lord of the Rings) because the reader is already familiar with many foundational elements of The Hobbit before they ever open the book. That’s because these are a near universal familiarity with fairy tale tropes. We don’t need to know the origin and history of Smaug - only that he is a dragon and dragons crave gold. Goblins are dark-dwelling troublemakers. Trolls are the big, dumb brutes we’ve always known them to be. In fact, the only oblige exposition dump we get that isn’t integrated into the narrative structure of the novel is the initial description of hobbits themselves! Our adversaries are familiar ones.

The Lord of the Rings, by contrast, constantly has the forces of evil invading places of safety. The Nazgul prowl the Shire and then Bree. The Uruk-Hai assault Helm’s Deep. The Armies of Mordor assault Minas Tirtih. There is no civilized place of safety in The Lord of the Rings - not even from the outset of the narrative. This makes that world a place that has little inherent safety - unlike The Hobbit where pockets of civilization and comfort can (for a long time) be found just a chapter away. Lord of the Rings assaults us relentlessly with dangers that are unknown, exotic, and therefore all the more threatening because of their inherent lack of familiarity.

All of this is to say I think that the world of The Hobbit when divorced from The Lord of the Rings is a masterclass in world building for a tabletop roleplaying game. It has a very specific flavor, is approachable and exotic at the same time, and while the PCs (assuming that at least Bilbo and Thorin were PCs) are tied very quickly to the narrative of the campaign. Once that narrative gets rolling, the focus remains on the areas of the world related to the campaign narrative. The rest of the world doesn’t matter to the player characters. Bilbo and Thorin and the others don’t need to know about Gondor, Rohan, Mordor, Fangorn, or any of that. Moria and Gondolin are flavor for the setting, nothing more. These things don’t need to be developed to create an engaging narrative for the player characters. The only one who knows anything meaningful about these places is Gandalf, who is an NPC with his own secrets and goals that don’t need to be revealed. Because they don’t need to be revealed, they don’t need to be established.

Not only is The Hobbit a master class in what can be done to build a world ripe for adventure - and just as importantly it is a wonderful example of what doesn’t need to be done. A fully approachable setting without the need to bury the reader (or your players) in endless pages of lore. The nature of the world is revealed as the narrative and the world unfolds. The only thing readers and players need to do is step out the door.

Since 1937 The Hobbit has been a foundational fantasy novel. A true open book.

A very thought provoking article and is actually a quite valuable way for solo RPG players to look at their world building. Many forget the Hobbit was written as a children’s book originally so that s why he kept it simple. The Lord of the Rings was written for adults.

I have been fascinated, almost obsessed, with the Rise Up Comus post since I read it years ago. I've wanted to create a setting that captures the feel of the 1937 Hobbit. Unfortunately, I'm not good at that sort of thing. And thanks for this post. It has me pondering things about it that I hadn't thought of before.